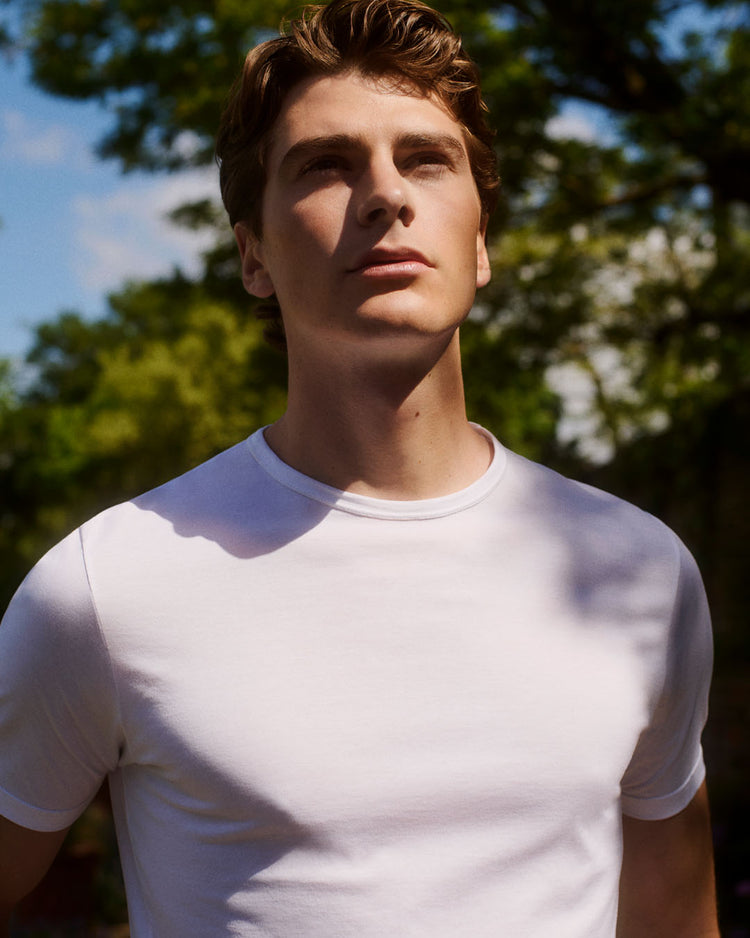

Sunspel Icons - The Classic T-shirt

A cultural icon and an everyday essential, the Sunspel Classic T-shirt is the foundation of every man’s wardrobe. Sunspel has spent the last 100 years perfecting it and each one is still handmade in our historic factory in Long Eaton, England.

|

Sunspel began making T-shirts in the early 1900s. We’ve supplied the world as the T-shirt has evolved from underwear to outerwear, from symbol of youthful rebellion to everyday wardrobe staple. We’ve spent over a century refining every aspect. Crafted in a luxurious extra-long staple Supima cotton for unparalleled softness, comfort and durability, the Sunspel Classic T-shirt has a classic fit and only the most essential details. Worn by modern icons from the Rolling Stones to David Beckham, it is widely recognised by leading fashion stylists as the best T-shirt in the world.

Sunspel was founded in 1860 to create luxury underwear. Using innovative technology, we developed new fabrics and styles designed to be comfortable in hot climates. By the early 20th century, we were creating a wide range of undergarments from the finest wools, silks and cottons. This included the simple, lightweight, short-sleeved ‘vests’ that we would now recognise as the earliest forms of the T-shirt. We crafted ours from Sea Island cotton, the world’s finest and rarest cotton, making these the first luxury T-shirts in the world.

|

In 1937 Sunspel moved from Nottingham to Long Eaton, where we remain today, and in the following decades, the simple, crew-neck style, pioneered by Sunspel, made the transition from practical underwear to iconic outerwear, immortalised in 1950s Hollywood. Now the T-shirt is ubiquitous. It’s the most fundamental wardrobe essential – seen everywhere in the world. Sunspel has been part of this icon’s story since the very beginning.

At our factory in Long Eaton, we’ve spent over a century refining every element of the Sunspel Classic T-shirt. One of the most important parts is the fabric we use, a unique Sunspel development known as Quality 82.

|

For Q82, we source only the highest quality extra-long staple Supima cotton. Full supply chain transparency is essential to guarantee quality, and we select each strand from a single Californian farm. This farm, family-owned since 1920, produces the finest cotton available while also maintaining strict environmental standards. The raw cotton is combed to remove imperfections, twisted together to create a fine, strong thread then passed over a flame, resulting in a luxurious yarn. The final Q82 fabric is knitted on a circular machine where blowers remove loose fibres, leaving a flawlessly smooth finish.

The T-shirt is handmade in our factory in Long Eaton, England, our home since 1937. The craftsmanship practised here is exceptional. Working with our lightweight Q82 fabric is a highly specialised skill, requiring years of expertise to master and many of our craftspeople have worked with Sunspel for over 20 years. Many come from families that have worked with us for generations.

|

|

The making of a Sunspel Classic T-shirt involves 12 meticulous processes, with 15 recorded quality control checks. Each garment is worked on by 10 different craftspeople and a specialist worker oversees every step, from fabric cutting to stitching, pressing, and folding. Quality control is ingrained in every aspect of production and each T-shirt is finished with a sticker bearing the name of the artisan who performs the last inspection, a final mark of quality and craftsmanship.